Surfing the Linux kernel

Syscalling for execution

the exec system call has many types (as shown in the diagram) but here, we’ll be discussing a summarized overview of how these work. Basically we dealing with executing binaries or scripts through the Linux kernel here through exec and its similar syscalls. But before we understand how such syscalls are defined in Linux source code, we need to understand one thing: pointers

pointers are variables that point to or store the memory address of another variable. Hence they “point to” the data of that variable.

Here’s an example of execve definition:

SYSCALL_DEFINE3(execve,

const char __user *, filename,

const char __user *const __user *, argv,

const char __user *const __user *, envp)

{

return do_execve(getname(filename), argv, envp);

}

This is a 3 argument definition, now why i mentioned pointers before is crucial to understanding the arguments. const char __user *const __user * means we are defining a pointer in kernel space that points to a constant valued pointer defined in user space that points to a character in user space. argv is the array of arguments and similarly envp is the array of environment variables (like PATH)

Binary format handlers and linux_binprm struct

When we are loading the executable, a struct (or user-defined data structure that can store multiple basic data types) called linux_binprm is created to store the metadata about that executable, like argument and env variable counts, filename, and then a buffer that will store (presently) the heading 256 bits of that file for identification of the binary format.

To identify the binary format, we have pointers known as binary format handlers, these are defined in files under the fs directory in the kernel source tree, and we iterate through these binfmt handlers to check which one matches the information in linux_binprm

Kernel modules

Kernel mods are extensible chunks of code that can add to an existing kernel’s features. We can add our own binfmt handlers through kernel modules.

Fancy things aside, here’s a diagram of files, libraries in the Linux source tree that determine what does what when it comes to dealing with executables.

Security, Security, SECURITY!!!

We have a few security checks in the entire process before and after loading the executable.

https://nvd.nist.gov/vuln/detail/CVE-2009-0029

Magical ELFs

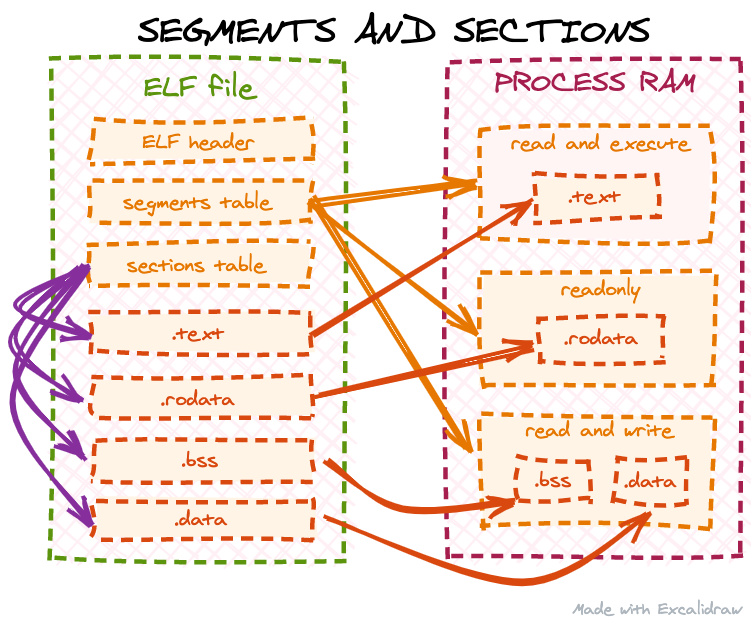

ELFs stand for Executable and Linkable formats, they are one of the most common executables in Linux.

Some parts:

ELF Header: contains metadata about entry point, instruction-set, dynamic/static linking instructions, etc.

Program Header Table/Segments table: how to load and execute during runtime.

Section Header: contains info about sections of the PE (portable executable) for better debugging and organisation

The program header tables contains a series of entries with header types, here are the common ones:

PT_LOAD: Data info to be loaded

PT_NOTE: Metadata (copyright, version)

PT_DYNAMIC: dynamic linking info

PT_INTERP: ELF interpreter path

Let’s talk about the parts mentioned in the Section Header:

.text: the

.textsection typically contains the executable code of the program. It is where the compiled instructions reside, and this section is loaded into memory during program execution..data: global variables, static variables

.bss: local variables

.rodata: read-only globals

Static Vs. Dynamic Linking

Dynamic Linking and DLLs

On Linux, libraries that are used for Dynamic Linking are saved as .so (shared object) files. Whereas on Windows, we call them .dll (dynamic link libraries)

When executing, the OS figures out what libraries are needed by going through the ELF Header and Program Header Table. If the program is dynamically linked, we need to deal with another program called the “ELF interpreter”. When loaded, the kernel pushes arguments and env variables into a process stack and sets a pointer to the start of executable code then the syscall is made. Registers are cleared, Kernel stores current register values to another stack before the syscall though. After the syscall, the kernel returns to user space and restores the register values from that stack and jumps to the stored instruction pointer in userspace. NOW, the ELF interpreter is executed and current process is replaced. Everything cycles for this one as well.