CPU Registers

Registers is a small amount of fast storage element into the processor. It is faster than cache memory due to the smaller size and proximity with the CPU itself.

We will use the GDB or GNU Debugger for demonstration purposes here.

(gdb) info registers

rax 0x0 0

rbx 0x7fffffffe3c8 140737488348104

rcx 0x7ffff7f9a680 140737353721472

rdx 0x7fffffffe3d8 140737488348120

rsi 0x7fffffffe3c8 140737488348104

rdi 0x1 1

rbp 0x7fffffffe2b0 0x7fffffffe2b0

rsp 0x7fffffffe2b0 0x7fffffffe2b0

here rax is a register variable. Where its value is 0 at the moment.

Understanding Assembly (skim-perspective)

All code once compiled/interpreted completely, is basically converted into machine code or assembly language. Although it is quite difficult to understand, we can point out certain patterns in it. Let's take a look at this assembly dump here:

(gdb) disassembly main

0x00000000004005ea <+45>: call 0x400490 <printf@plt>

0x00000000004005ef <+50>: mov -0x10(%rbp),%rax

0x00000000004005f3 <+54>: add $0x8,%rax

0x00000000004005f7 <+58>: mov (%rax),%rax

0x00000000004005fa <+61>: mov $0x4006da,%esi

0x00000000004005ff <+66>: mov %rax,%rdi

0x0000000000400602 <+69>: call 0x4004b0 <strcmp@plt>

0x0000000000400607 <+74>: test %eax,%eax

0x0000000000400609 <+76>: jne 0x400617 <main+90>

0x000000000040060b <+78>: mov $0x4006ea,%edi

0x0000000000400610 <+83>: call 0x400480 <puts@plt>

0x0000000000400615 <+88>: jmp 0x40062d <main+112>

In here, at the 0x00000000004005ea or the 5ea line location/memory address, the <printf@plt> statement basically means that a printf() function is being called.

When we look at the manual for the printf() statement, it means that some message is being printed on the console.

Hence, we can conclude that one does not need to know assembly in depth to understand its code.

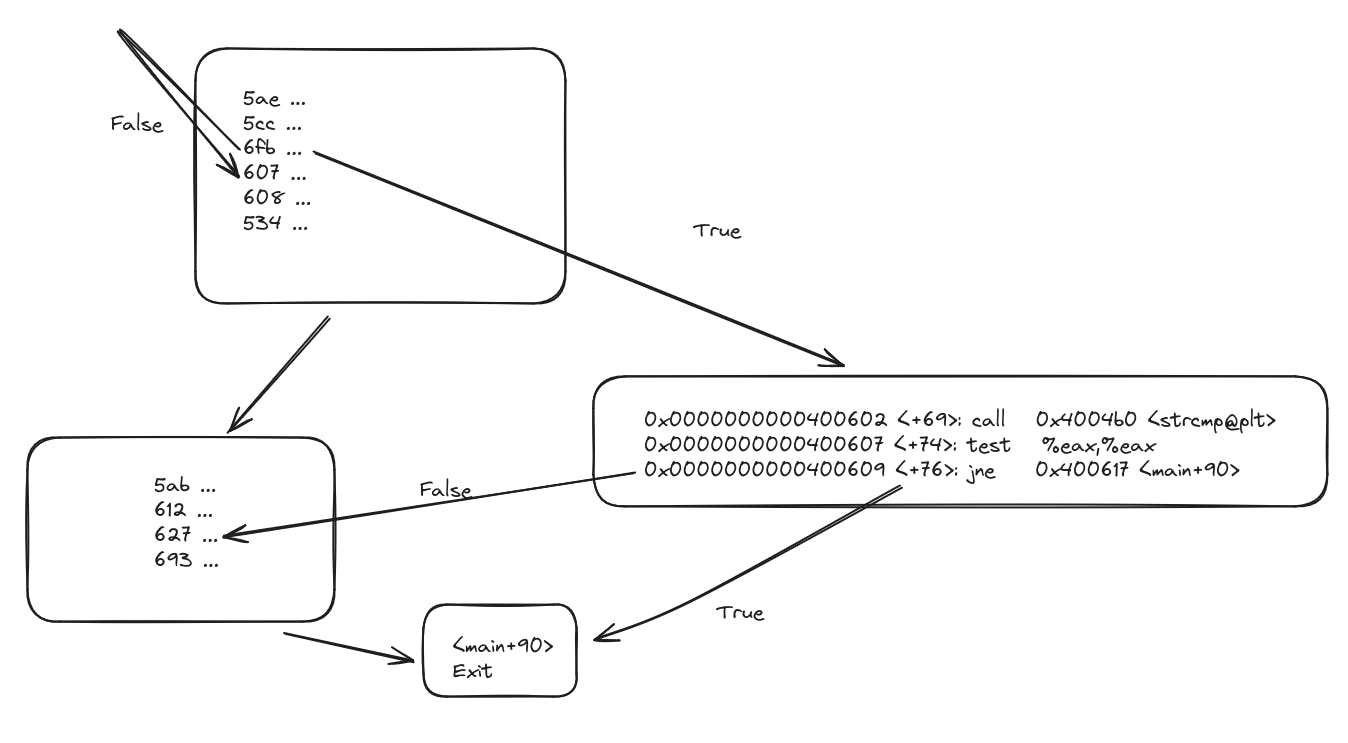

Constructing control flow and branches

let's take a look at this particular section from the assembly dump:

0x0000000000400602 <+69>: call 0x4004b0 <strcmp@plt>

0x0000000000400607 <+74>: test %eax,%eax

0x0000000000400609 <+76>: jne 0x400617 <main+90>

a function of strcmp() is called which means two strings are compared (according to its definition), two variables are being compared and checked if they are the same or not. In 0x0000000000400607 <+74>: test %eax,%eax, we are checking the value of the register variable eax ,which denotes the first 32 bits of the 64 bit long capacity of the 64 bit variable rax we encountered in the output displayed at the top in 'CPU registers'.

In the last line, the jne command translates to jump when false with the specification to jump to the memory address of the main+90.

Just like that we construct a diagram or flowchart for the control flow of the entire program:

(please note that this is not accurate or usable code)

Cracking

Cracking is the process of breaking into and executing portions protected or protected code. It is considered a part of reverse-engineering.

From the previous topic, we can easily look into the register values, and the functions to take the control flow pointer or rip to that particular location of code which we wish to access. In the given section, we can make adjustments to rax by changing the value of eax to 0 through GDB or some similar debugger to make the program think that we the strcmp function is returning the FALSE value. So when we run the program from that particular set breakpoint, we will be able to access that particular portion of code that is only run if strcmp return FALSE.

How can we relate this to a real-life example? Password-protected applications is the key.